The Ghost Dance (Nanissáanah, 1890) was a ceremony incorporated into numerous Native American belief systems. According to the teachings of the Northern Paiute spiritual leader Wovoka, proper practice of the dance would reunite the living with spirits of the dead, bring the spirits to fight on their behalf, end American westward expansion, and bring peace, prosperity, and unity to Native American peoples throughout the region.

On January 6 the exhibit “Occupied Wounded Knee 1973” opened at The History Center in Cedar Rapids.

This exhibit commemorates the 50th anniversary of the 1973 occupation of Wounded Knee, South Dakota and the subsequent trials.

Also featured is the role Linn County played in these trials of American Indian Movement members.

Our nation’s familiarity with Wounded Knee began with the December 29, 1890 massacre of almost 300 Lakota people, mostly women and children, at the hands of U.S. Army soldiers. The slaughter ensued as soldiers tried to disarm a band of Lakota.

Connected to those killings was the rise of Nanissáanah (Ghost Dance), a ritual which was deemed threatening. Nanissáanah’s mysticism was not understood, therefore it appeared menacing to the government.

Nanissáanah implored the Old Ones to rise again and help return the buffalo and land to the Lakota People. The return of buffalo was necessary, as it was a food source essential to tribal life. It was government practice to exterminate buffalo, thereby depriving this food staple from the Lakota. As nomadic people, access to land was also essential to tribal livelihood.

Thus, Wounded Knee became a symbolic Lakota holy site. In 1973, the American Indian Movement (AIM) confronted what they considered corruption in tribal leadership, doing so through the occupation of the village of Wounded Knee on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota.

During that occupation, two FBI agents were killed. Someone had to be held accountable, hence the trials in Linn County which was selected as a “neutral” venue away from the Dakotas.

A local connection unfolded as Mount Vernon attorney Fred Dumbaugh provided local material assistance to the defense’s legal team, all of whom were from out of this area.

The fact of the Wounded Knee massacre in 1890, and the uprising of 1973, raised curiosity within me.

In 1890 and again in 1973, the voices of ancestors were always central to actions. Listening to the wisdom and summoning the spirit of the Old Ones was a form of prayer, be it through dance or action.

I imagine what the Mount Vernon area looked like before white settlers arrived some 200 years ago.

The land here must have been teeming with buffalo, elk, and deer. Forests were lush and prevalent, surrounding meadows filled with colorful, diverse blooms. Fish flourished in the clean water of streams and rivers. Great flocks of birds filled the sky.

Evidence of the Old Ones’ presence surrounds us, be it burial mounds at Palisades-Kepler State Park or near Abbe Creek School, or in the arrowheads which still rise in cultivated fields.

What lessons could these ancestors teach us now? Who are our community’s contemporary wisdom keepers to whom we should listen?

The History Center’s exhibit runs through June 2023. It is worth seeing… and knowing. Ultimately, it becomes our story when we learn from the Old Ones, present and past.

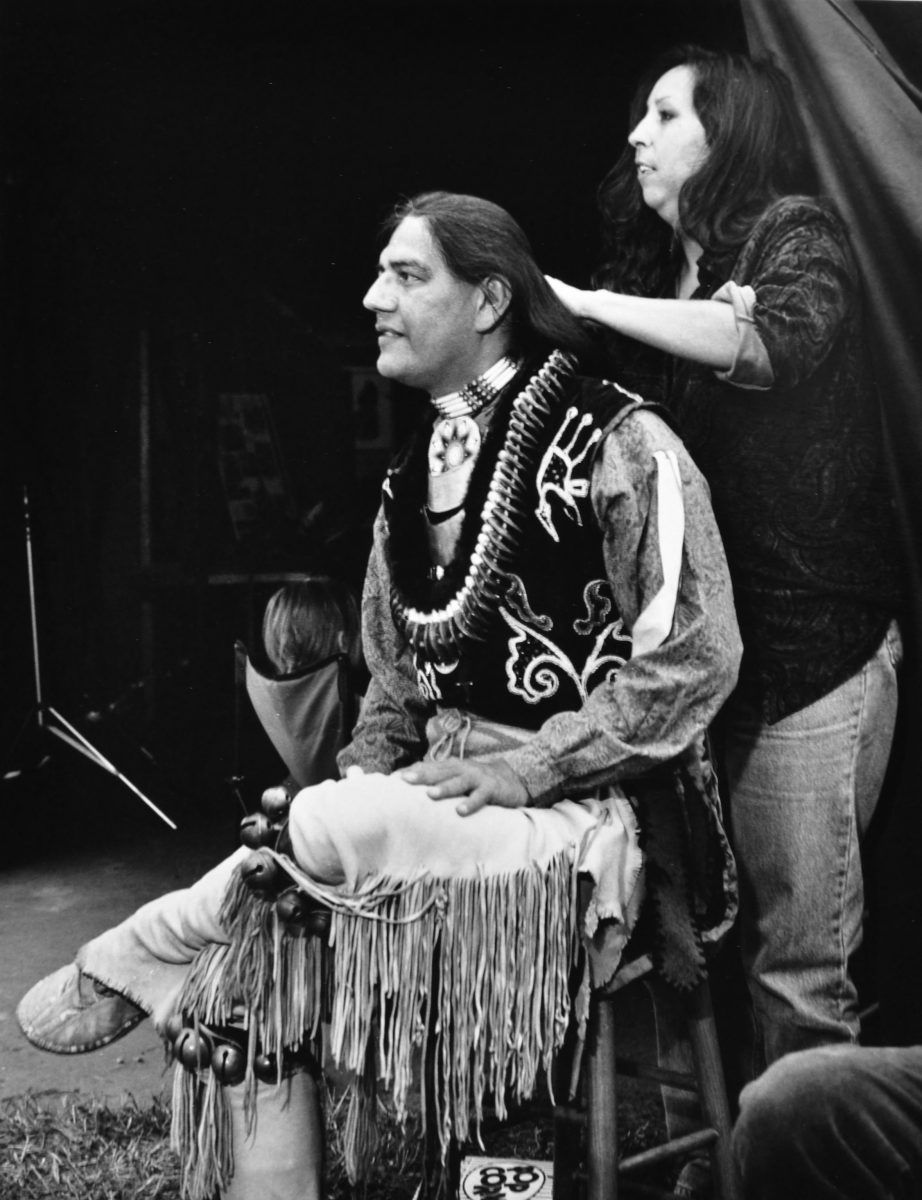

Johnathan Buffalo is tribal historian of the Meskwaki Settlement near Tama. Suzanne Wanatee is preparing Johnathan’s hair for the 1999 annual summer powwow. Johnathan is a spiritual man of quiet wisdom. His mother and my mother died within a few weeks of each other. Johnathan’s words were profound: “When we lose our mothers, we truly become orphans.”